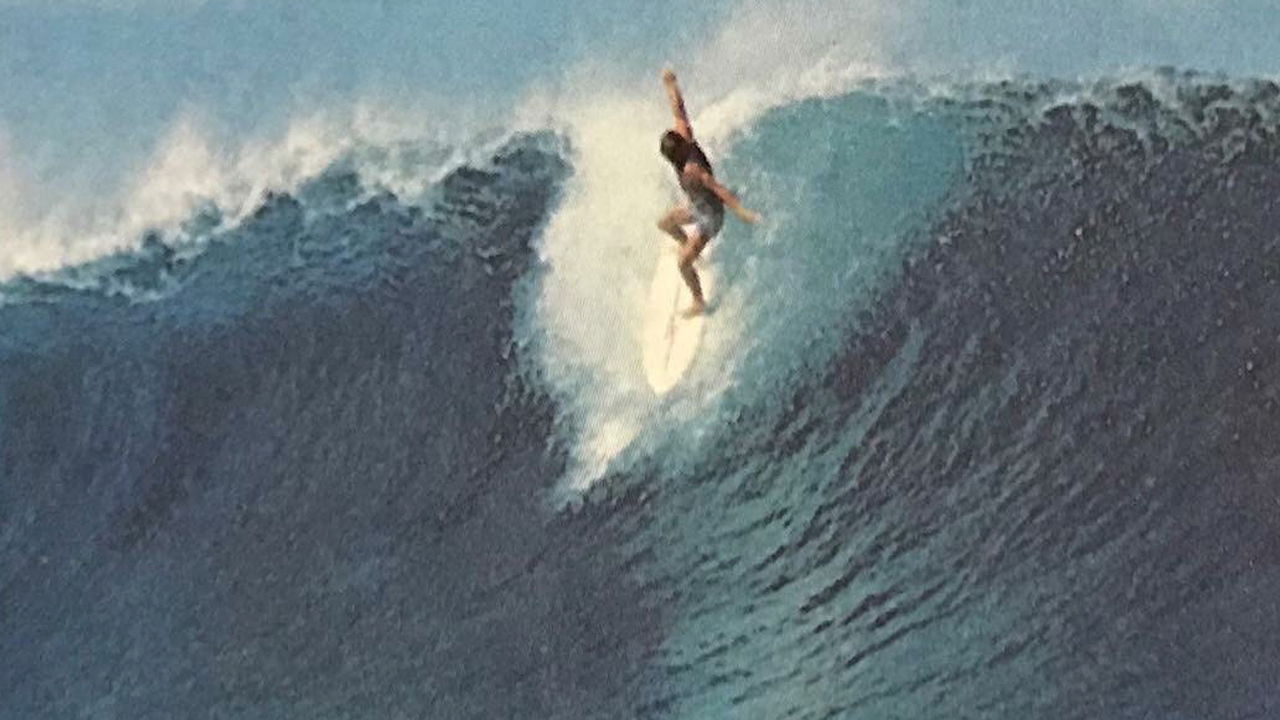

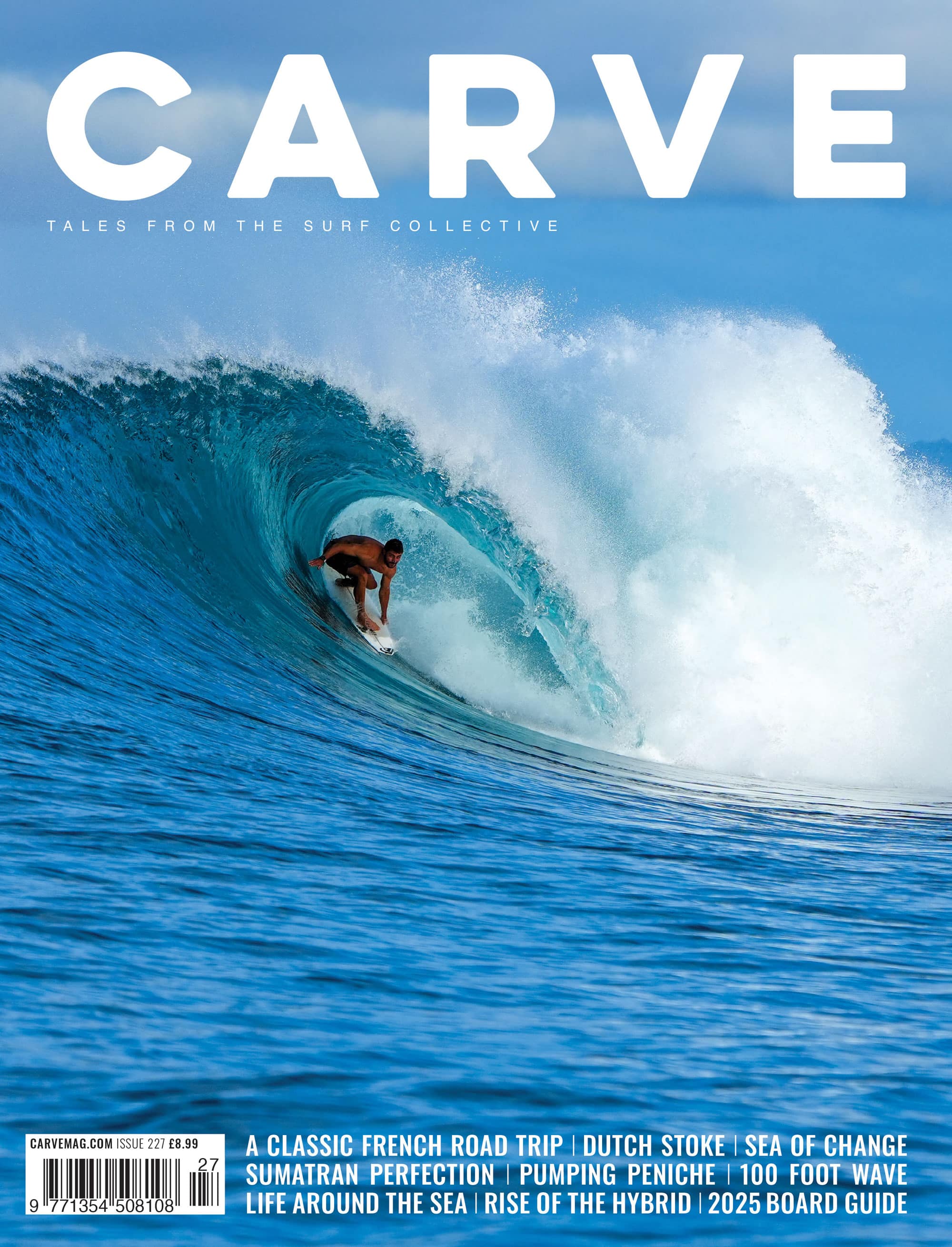

Ted at Padang Padang Photo: Hoole/McCoy

Ted believed. He had faith. Excalibur was real. And if it wasn’t, well, then he would make it real. He would take a myth and insert it into everyday life and thereby transform the world. He would, in a way, become Arthur. Or at least Merlin. Perhaps he was indeed, if Arthur had any substance to him, through the ancient Coventry family, a descendant of Arthur. He surely had a drop of Arthurian blood running through his veins. Maybe every true born Englishman did. In the absence of a handy stone that he could miraculously draw the sword out of, Ted talked Paul Holmes, an expatriate Brit who was then editor of Surfer, into funding a real sword, to be forged by the jeweller Mitch Nugent in England. A blade made of steel and a hilt cast in bronze and silver and encrusted with sea creatures set against some trop- ical backdrop. “A treasure any king would be proud to wield,” Ted announced to the world. Engraved with the words, “The Spirit of Surfing”, it was to be awarded to the winner of the Excalibur Cup, a charitable surfing competition dreamed up by Ted. “According to legend,” he recalled, “Excalibur could not be defeated in battle, as long as the user would only fight for right and justice, a noble concept.” Only Queen Guinevere was missing – but surely, reasoned Ted in his mystic logic, once Excalibur existed then Guinevere could not be far behind. As it once had been, so it must be again: the present moment appeared as only a temporary falling away from perfection, a transient and intermediate state that could not endure.

The idea first came to Ted in Australia, he said, when he was having a game of tennis with Rabbit Bartholomew. Singles. Man-on-man. In a classic lightbulb moment, Ted realised that the very same man-on-man concept could be applied to surfing. Eureka! A very fine idea. So fine, in fact, that it had already been espoused by the ASP, the Association of Surfing Professionals. The Excalibur Cup would therefore, in effect, be a rival to the ASP tour, the grand prix circuit. And, to some extent, an antithesis, almost an antagonist. It was Excalibur vs the ASP. Because the ASP was, as its name implies, “professional” and surfers expected or at least hoped that they could earn a living – or at least pay their expenses and keep the wolf from the door – by surfing under its auspices and participating in its contests.

Whereas Excalibur was all about charity.

As Paul Holmes, then editor of Surfer magazine, put it, “Ted was going in the opposite direction”. As was his wont.

Nobody would win any money, nobody would be paid a penny, all proceeds would go directly to good causes, entirely omitting the shrewd and well-paid middle man. Excalibur was a vision of how the world might be. The ASP was simply an extension of the way the world is. Surfing as myth and legend – or surfing as a form of materialism, a career, in which you could work your way up the greasy pole. Ted tried to belong to both worlds, but his heart was really in Excalibur, the chivalric code. Chivalry was not yet extinct.

“To gain, one has to be willing to give.” Such was the founding principle of Excalibur. The idea was to encourage or enable underprivileged or disabled kids to get to the beach and enjoy the “spirit of surfing”. A non-profit foundation was formed, its mission “to promote the sport of surfing, teach its participants the chivalrous concept of doing for others, and to raise funds for less fortunate individuals so they may enjoy their lives.” At first, Ted’s idea took off. He found established surfers willing to give of their time and energy and prowess in a quest for virtue and altruism. It was true Round Table stuff. These were one-day events involving the top eight surfers in the world. They pulled in the crowds and they raised thou- sands of dollars for youngsters. The inaugural event in 1982 at Burleigh Heads took place amid six-foot barrels and was won by Hawaii’s Michael Ho, beating Australian Cheyne Horan in the final. Perhaps the result could even heal the wounds inflicted by the Bustin’ Down the Door war and thus usher in everlasting peace. Ted recruited Australians who were towering figures in the sport such as Derek Hynd and Mark Richards to do the live commentary. Not to mention Australian “Playmate of the Year”, Lyn Barron.

When Ted moved back to America in 1986 he took the Excalibur Cup with him. The “Excalibur Cup Foundation” was formed, “an independent non-profit corporation”. He had a vision of “getting the attention of all America” and raising at least $50,000 for good causes (“Special Populations”, “Monmouth County Seals”). Events took place, with reasonable success in Florida (three-foot barrels and offshore winds) and further north in New Jersey. “Much like in the legend of old,” Ted wrote when 15-year-old Kelly Slater – the future many-times-over world champion – took the title, “the youngest proved the most worthy.” They picked up celebrity support from actress and old flame Heather Thomas (by then the star of a TV show, Fall Guy) and Jack Sonni, guitarist with Dire Straits, who was a recent convert and enthusiast. Ted even invited the Prince and Princess of Wales (ie Charles and Di) to hand over the prize (a very pleasant letter from the Palace in response regretfully declined).