The Sound Of Senegal

words by SAM BLEAKLEY photos by JACK JOHNS

Infectious Music

As a lover of both African surf culture and music, Senegal has been on my radar for decades. So when the chance to help produce a West African project arose with Finisterre, I was in my element. I’ve cut my teeth exploring surf on this continent, starting in sweltering cities with an irresistible buzz, then mapping pointbreaks through the likes of Liberia, Sierra Leone, Mauritania, Western Sahara, Algeria, Kenya, Madagascar and beyond. Outside of the more established surf communities in Morocco and South Africa, the rewards are the charisma of the people, their resilience in the face of adversity, and the grassroots surf scenes that steward long and lonely pointbreaks with an infectious joie de vivre. These underground scenes excite me far more than the established surfing coastlines that have produced our world champions. Going down to the basement places and the cinder-glow they exert there are untold riches. But existence here can be challenging and confusing, nights hot and pungent like sulphur. The music follows the same tracks, right in your face, up close, hammering on the chest and ringing in the ears. But you always come back for more because the beat of these places is not just infectious but hypnotic. ‘Should I stay or should I go?’ ask the Clash. With an African rhythm, you are pinned.

I danced my way across a series of easy to ride sets and watched the fisherman bring in a fresh catch on their narrow pirogue.

It still blows me away that the opening three countries in Bruce Brown’s mid-1960s trailblazing The Endless Summer – Senegal, Ghana and Nigeria – have attracted so few surf travellers. Today these nations have vibrant local surf scenes. And West Africa has a rich, often overlooked, history of ocean savvy coastal culture. While we think of pre-colonial surfing as a Polynesian pursuit, look at the earliest European reports from West Africa from the 1600s, and you’ll find descriptions of locals ‘swimming like fish’ and riding prone with expertise on small pieces of wood and in canoes. In the most detailed account of early African wave riding in 1823, Englishman John Adams described kids in modern day Ghana on ‘pieces of broken canoes, which they launch, and paddle outside of the surf, when, watching a proper opportunity, they place their frail barks on the tops of high waves, which, in their progress to the shore, carry them along with great velocity.’ Perhaps under different economic opportunities following post-colonial independence, these coastlines could have already fostered our world surfing champions. Maybe they will in the future. Watch this space.

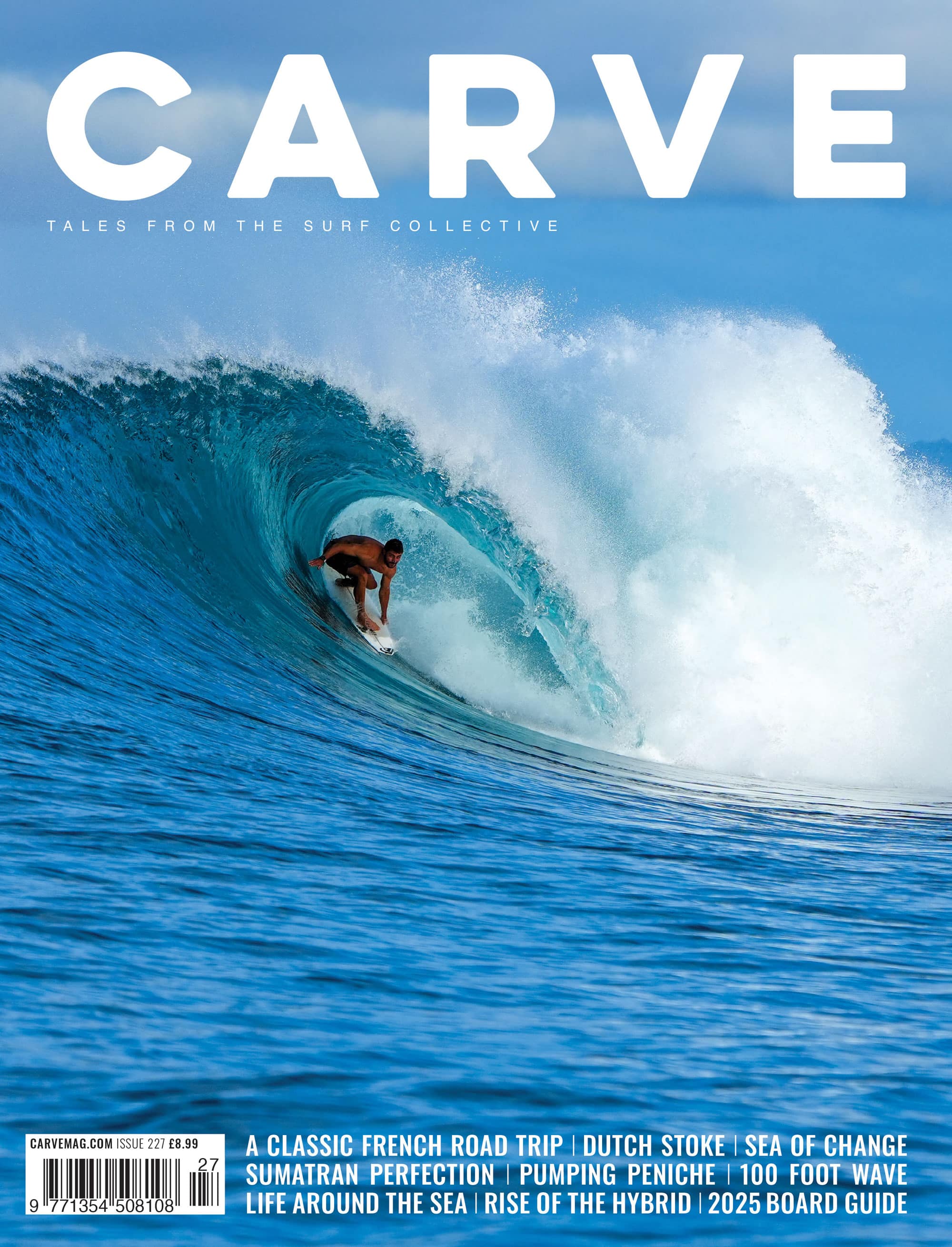

I arrived a day before the rest of the Finisterre crew to surf at N’Gor right on the very western tip of Senegal. It was ridden by Californian’s Mike Hynson, and Robert August for the opening travel sequence of The Endless Summer as the trio set out on a three month long around the world trip in ‘search for the perfect wave’. They arrived at LA airport for the flight to Dakar wearing suits and ties. That’s how you travelled then. They scored sizzling Senegal, blistering bluewater sections bouncing over shallow boulders, and refracting around N’Gor island, a short boat ride from Dakar on the mainland. Back then it was dotted with just a handful of buildings. Today N’Gor is a tourism hub and a labyrinth of bougainvillaea-lined guesthouses. But the lure to explore is as strong as ever.

I danced my way across a series of easy to ride sets and watched the fisherman bring in a fresh catch on their narrow pirogues. Back on land, I met a handful of local Senegalese surfers eager to share information on board design. But I wasn’t the first from the Finisterre family to arrive: filmmaker Luke Pilbeam and his partner Sophie Bradford (secondary school languages teacher and model) had already spent a week on the island. We traded stories about skirting the urchin-infested reef breaks, then met up with Jesper Mouritzen, the owner of N’Gor Island Surf Camp, and ferried back to the mainland to meet the rest of the crew, while Sophie flew home for the new school term. The travel band united in downtown Dakar – South African Apish Tshethsa, Australian Noah Lane and British septet David Gray, Sophie Kelly, Suzi Winter, Amy Brock-Morgan, Danielle McDonald, Jack Johns and Luke. Jesper helped us organise a van with an ice-cool driver called Modo, and guide Gabriel. Both are ethnic Lebou from the fishing cultures of the Dakar peninsula. There are 38 languages spoken in Senegal, and Modo and Gabriel speak Wolof, tracing back to the mighty Jolof Empire that ruled West Africa from the 13th to the mid 16th century before European colonialists introduced French into the fabric of the community. Today most Senegalese speak excellent French, so this is a lingua franca for travellers.

Land of Teranga

Senegal is known as the ‘land of teranga’, which is the Wolof word for hospitality. This is the great gift of travel, the exchange of trust through hospitality and sharing. You are a guest, sometimes uninvited, of those who already live here. You enter a circle of hospitality that must be honoured and not broken. The host invites, the guest reciprocates in the terms that the host sets. ‘Hospitality’ has the same root as ‘hospital’ – you are symbolically sick and cared for as a guest. But as a travelling guest, you can help the host to offer hospitality simply by being tolerant of difference, aware that there is much to be learned through suspending one’s baggage and celebrating cultural exchange. When experiencing new places you need to be fully grounded in your senses. Do not challenge, but adapt. Stick with your animal instincts and keep calm. Then relax into the place as a guest, not the new owner. Gabriel revealed a broad smile that lit up every conversation, and applied his lanky frame to help us load our gear into the van, while driver Modo subtly readjusted his sunglasses, unruffled his lapa fabric patterned shirt, and we set off into the steaming streets of Dakar: a feast for the senses. The Republic of Senegal stands proud on the west coast of sub-Saharan Africa, surrounded by Mauritania, Mali, Guinea and Guinea Bissau, and a 700 km long stretch of convoluted Atlantic Ocean, cold-watered in the winter and warm-watered in the summer. The capital has a population of four million bursting at the seams. As we zigzagged through the traffic, the city appeared to pulse with the sound of the national mbalax music, old Peugeot taxi stereos and street bars blasting out infectious rhythms that have divine origins in ancient initiation ceremonies, now layered with frenetic, stuttering drums, and luminescent lyrics. Modo turned up his radio as Youssou N’Dour played, the grand champion of the mbalax genre. In the last jam of traffic we passed vendors selling peanuts (the iconic cash crop of Senegal), sipping sweet attaya tea, and wearing fabrics so bright and brilliant they are near-blinding. Then the city limits ended, and the road opened out seamlessly to Toubab Dialaw and our rented apartment.

We awoke to a bone dry morning, the hamattan northeast wind reigning supreme, filtering the sunrise with Saharan sand.

In a region with exceptionally rough neighbours, Senegal remains politically stable and progressive. This is in many ways thanks to the very first president following independence from French colonial rule in 1960. Leopold Sedar Senghour was a poet and politician and established state funding for art that fed into the great flowering of music. Like Mali, Senegal already had a long history of griots – storytellers, poets, praise singers and troubadours who played the West African 22 string harp known as the kora. As a new generation of post-independence artists were inspired by Cuban music, they mixed this with their sabra dance rhythms, and mbalax flourished. This was a sound of freedom where liberation from European colonialism allowed identities to be reclaimed. The music was infectious and uplifting, embodying the characteristic optimism of independent Africa. But for Senegal’s neighbours, the legacy of the colonial period had created terrible burdens. As the tide of independence receded, so previously masked ethnic rivalries flared up. Instead of peaceful progress, bitter conflicts blazed. Many places became war-torn and fell apart for decades to come. But not Senegal. It remained a beacon of hope for the continent, politically stable and culturally vibrant.

Hamattan Wind

We awoke to a bone dry morning, the hamattan northeast wind reigning supreme, filtering the sunrise with Saharan sand. The apartment looks out over a limewater Atlantic, and the titanium light was bouncing off the drumhead of a rising swell. The so-called Petite Cote is a contrast to the windswept Grande Cote to the north (where the Dakar peninsula is situated). It feels more Mediterranean than Atlantic, but the bridge was a rapidly building northwest swell linking Europe and the Atlantic in a huge halo of saltwater spray. Taking advantage of the cooler morning air, local men trained for the Senegalese wrestling (and national sport) known as lutte, while groups played football, proudly wearing the national flag colours of green, yellow and red. Fresh from Cape Town, football loving Apish was straight into the cauldron of keepie-ups and one-touch-passes. “It’s my first trip to another African country, so I want to meet the locals,” he said as he joined the action. After a solid kickabout, Apish explained that is was through football that he found surfing, and became one of the founders of the ground-breaking Waves for Change program that uses wave riding to provide therapy for young South Africans from violent communities. “I came from a troubled background in the township of Masiphumelele and started teaching other kids football when I was 15 to help stay positive. British surfer Tim Conibear had just moved to Muizenberg and wanted to use surfing as a form of therapy. He saw that I was passionate about using sport to help kids, so invited me to surf. I was hooked. Learning to surf was an opportunity to build confidence, and I love sharing this with others.” Apish’s passion for people is infectious. He is a bridge builder, connecting communities.

Toubab is a bohemian beach town peppered with painters, creatives and dance schools. The neighbourhood is elegant, with cobbled streets and art makers working alongside fruit sellers. While some of the crew travelled with Modo and Gabriel in the van to explore shooting locations for the coming days, the rest of us strapped our boards onto a battered old Peugeot 505 taxi and headed south to find a sheltered pointbreak that could hold the now restless swell. We meticulously inspected every lookout point sashaying through fishing communities who all seemed to have a clothing maker working outdoors with local fabric; some tie-dyed using mahogany, acacia and kola nut to produce vivid prints. Amy runs the repairs workshop at Finisterre, and also hand-crafts beach kit using re-purposed materials, working with fabric not only aesthetically and functionally, but also as a form of therapy, often through community workshops for women to express emotion and develop resilience. Amy also speaks excellent French, and quickly connected with the local artisans, who also not only make things to sell but as a form of meditation, a fabric for life. Fuelled with these creative threads, Amy was first outback at a fold of coast that stitched a playful right and long left point. A little later, the rest of the crew joined us, so we feasted on the evening light, lit a bonfire on the beach, and surfed again until the sun poured whole into the citrus coloured water and planned the dawn patrol around the dying embers. But this was just the lemon next to the pie: the swell was set to peak in the morning.

Twelve Wave Sets

We travelled north as twelve wave sets marched down the coast. Everywhere was closed out, until one particular bend in the beach revealed a heaving close-to-shore muddy-water barrel that caused Noah and Jack to panic with excitement. Photographer Jack didn’t come on the project to surf, but he is one of the best bodyboarders in the world. The knowledge Jack has of the innermost limits of the tube translate easily to standing up, so when I loaned him my 6’6″ egg, he joined Noah as the crowd gathered in awe at the bravery of the surfers. This is an active fishing community, the day’s work prevented by the huge swell, so they immediately recognised the danger. But while Dakar has an emerging local surf culture (backed up by surf tourism), further south, close to Toubab, subsistence fishing is still the norm. Noah and Jack timed the sets and scratched through the shorebreak as kids gathered in huge wheeling groups, eager to witness the first ride, the anticipation building like an electric storm. Noah was deepest as an ominous shadow rose up violently, and he dropped into a bomb, the takeoff appearing in slow motion as he angled back up into the boiling cauldron mid-face and was in the throat of a large barrel. For a moment time stood even slower as he stood tall and then flexed his knees working his twin-fin channel bottom to perfection, snaking deep inside the pit, then emerging underneath a furious blast of spit, to straighten out in front of the now booming closeout. The entire beach erupted with joy. As Noah walked back up the sand to avoid the longer paddle and brutal current, he was mobbed by the kids and fishing families, who heralded him as a hero, and a troubadour. We’ve come to know the skillset of Noah surfing sledgehammer sections in Ireland. But this was magnified by the joy of a riding in front of kids who had never seen stand-up surfing before, possibly at a never-before-surfed-spot. Under both surfers were interesting boards built by interesting shapers. Surfing has always been a marriage of form and function. The combined craft of the shaper and glasser precedes the rider who turns craft into art. Markie Lascelles built Noah’s twin-fin at Beach Beat. Jack’s egg was designed by recently re-formed West Penwith brand Inner Visions and crafted by Chris ‘Bro’’ Diplock. These two boards were personalities. There is something about having a twin-fin and egg that smooths out not only your surfing but your psyche.

The entire beach erupted with joy. As Noah walked back up the sand to avoid the longer paddle and brutal current.

Rainbow Bridge That night, exhausted, the harmattan wind blew at gale force, and the next morning we travelled south to explore a landscape of low baobab studded hills close to Popenguine. Despite the now near searing heat of the late morning, we all embraced the opportunity to be close to the wise old baobabs. Lasting thousands of years, the baobab can endure seemingly endless periods without water. And when they do die, they rot from the inside and suddenly collapses into a heap of fibres. No wonder in African folklore they do not perish, but disappear, like magic. Popenguine is a magical place, home to a vast nature reserve managed by a collective of women’s groups. For the past thirty years, they have revitalised what was once a denuded patch of land, planting thousands of trees and mangroves, and consequently been awarded the Equator Prize for excellence in community-based poverty reduction through conservation and sustainable management of biodiversity. And the protected zone stretches two kilometres out into the Atlantic, like a rainbow bridge between land and water, that will now hopefully leave pots of untouched gold for generations to come. The swell continued to pump as we drove north the next morning towards the Almadies peninsula to surf Oukham, a world-class ruler edge right and bowling left framed by a white-walled mosque. In no time, Jack and Luke clambered up the hillside to get their take on this iconic break. The water here is deep indigo due to the change in geology. It’s shallow and fast, and the temperature is slightly cooler than down south, so we scrambled into summer suits and met the local fisherman with the ubiquitous, “Asalaa maalekum (Peace be upon you),” followed by, “Maalekum salaam (Peace with you also),” and paddled out as the mosque speakers announced the call to prayer. Senegal has long been the homeland of both Sunni and Sufi Muslims. Sufism is a more mystical practice noted for its attention to the reading of religious poetry, comparable to Zen Buddhism, Yoga in Hinduism or Kabbalah in Judaism, where a spiritual master, or sheikh, guides a group through the rollercoaster of life. A low ceiling of cloud that looked more like dark smoke moved in, hovering over a now heron-blue sea that at one moment was eerily calm, and the next, riddled with activity as sets rose, then raced in. The biggest waves were breaking at a high tempo, like a pianist making a run, a frantic solo, culminating in a succession of crashing chords. Amy guided us into the ledging lefts, hurtling into a slab of saltwater joy on her mint green shortboard. Apish paddled like lightning into the next wave, a deep smile etched on his face as he catapulted to the safety of the channel. It was solid enough to get the heart pumping. But for Noah, this was a cakewalk. He nonchalantly ducked under the curtain on takeoff, slicing into the open face, then cranking a billowing bottom-turn, followed by a classy hook under the lip and then a poised stall before he gracefully stepped forward to pull into a sneaky tube on the inside. Amy was on the next cascade, blaring out of a tube, trimming at triple time and just making the shoulder with a flourish of cymbals over the rock bottom. After trading licks on the lefts, we paddled over to the rights, stretched out to breaking point like elastic, then offering open walls for parabolic rail-to-rail carving perfect for the egg and twin-fin. And it’s on these sea-scores where the local crew stood out, improvising against this fast-moving Atlantic pulse as it raced to dump its energy onto the urchin-covered reef. After the surf, we traded contacts with the local crew and headed through Dakar for N’Gor island. Past trees on fire with smoking orange-red flowers, past the African Renaissance Monument that shows a family rising from a mountaintop and ambitiously heading towards the sea. Into the streets of the city, teeming with life, senses invaded by smoke, sewers and spices, khaki coloured dogs hanging outside tinfoil houses, sun-drenched windows filled with three suns looking out, bright faces born from the house shade, then markets and music fizzing over like a shaken soda.

We took a boat to N’Gor where the swell was seismic. It never goes flat here due to the 260 degrees exposure from the southeast to the north-northeast. The island was shaking from the shock waves, so we swam around the more sheltered lee, aside the bright-painted pirogues with red-yellow-blue-green patterns. The waves had turned even the lee into an ion charged whirlpool. The immersion immediately triggered a release of endorphins, serotonin and oxygen through our bodies. This is the power of moving water, now used worldwide to treat psychological health conditions through a sea healing that can boost self-esteem. In the salt-stain of the cliff edge, we watched in awe as out-of-control sets cracked the reef and crashed awkwardly into the channel. It looked very different to a week ago when I surfed it under small conditions, similar to the enticing The Endless Summer sequence. Of course, watching that film today the white imperialism leaps out, but when Bruce Brown made the movie in the grip of the socio-political tensions of the Cold War, 1960s world leaders could have learned a lot from this social icebreaker as surf travel was used to build bridges. No false diplomacy, just the universal language of shared adventure. Here surfing transcended politics in a search for a simple, often healing, cultural exchange. And these themes remain a respite from the haze of life-stress, offering a vital vitamin sea.

We walked into the rabbit warren alleyways to N’Gor Island Surf Camp, where the owner Jesper introduced us to his French-Tunisian wife Soraya and their daughter Mia. Jesper is from Denmark but fell in love with N’Gor when he arrived a decade ago, took over the dishevelled camp and injected new life into it. He has been a driving force for a much needed financial lifeline of international tourism. The camp now hosts about 1,000 surfers a year and is a leader in the new wave of surf tourism providers on the Almadies Peninsula – a six-mile stretch back on the mainland with 15 quality surf spots. Mour Mbengue and Kouka Ba, two of Senegal’s best surfers, are instructors at N’Gor Island Surf Camp. They are at the forefront of a thriving local crew, all inspired by Omar Seye, Senegal’s first pro surfer, who started aged 13, and now at nearly 40, owns the Rip Curl Surf Camp. Omar was at the helm of the recent WQS contest in Senegal, where Croyde’s Peony Knight finished in 3rd place. The most talented in the local scene is Cherif Fall, a trendsetter in the loose, electric and light-footed style of this crew, influenced by the cultural vibrancy that surrounds them. Khardiata ‘Khadjou’ Sambe is breaking new ground as Senegal’s best female surfer. She was taught by her uncle Pape Samba Ndiaye and now works for Malika Surf Camp in nearby Yoff, run by Marta Imarisio. There is now a buzzing scene now backed up by international contests and sponsorship opportunities. The future is bright for Senegalese surfing. Just listen to the music to hear the potential.