Carve started in the spring of 1994, a time when democracy finally came to South Africa, the Channel Tunnel connected our wet rocks to the continent, war raged in the Balkans, and the legend that was Ayrton Senna raced his last. The US and Russia also agreed to stop the nuclear dick swinging exercise and focused on not wiping us all off the face of the earth. Meaning Berlin returned to the folks of Berlin, armies left Germany, and the world breathed a sigh of relief after decades of Cold War-inspired overly tight sphincters. It was, in short, generally a time of positivity and hope. A pervading feeling that things might be alright. The internet was becoming accessible to the general public, and some bloke called Jeff Bezos started Amazon to flog books from his garage. He figured he’d go bankrupt soon enough unless this new-fangled internet thing caught on.

Into this new age of peace and harmony Carve was born. Wide-eyed and full of beans ready to literally rewrite what a British surf mag could be; a mag that would be punching on a world level, not a surfing backwater one. Stunning photography was, of course, the key to the project and surf photography, along with photography in general, was a very different scene to how it is now.

35mm single lens reflex cameras, (SLR) had been around since the turn of the 20th century, but it was the Nikon F, introduced in 1959, that perfected the concept. It became beloved by photojournalists and catalysed the transition from bulky, slow and unwieldy large format cameras to the reportage friendly SLR format that has defined the art ever since. It was a Nikon F that stopped a bullet for legendary British war photographer Don McCullin in Vietnam.

Manual focus, manual wind, film cameras were very much still in use when the mag started (this kid was rolling with a Canon AE1P in ‘94). So the hipster #shotonfilm thing happening now is harking back to an age not so distant in the rearview mirror.

The mag’s big lens in those early days was the Canon 800mm bazooka. No autofocus here pards, this weapon was manually focussed using the thumb wheels on either side. Now if you’ve ever played with a long telephoto lens these days, you’ll know that even with modern autofocus systems getting a speeding surfer in focus is tricky. Imagine doing it on the manual. It was a real skill, an ability that meant the guys that were good, cleaned up. Sports photography in the late ‘80s was dominated by the guys that could get stuff in focus, hard in surfing, even harder at an F1 circuit or football pitch. So much as our generation whinged when digital came along the manual focus mob were pretty bummed when autofocus came along — rendering their fine motor function skills irrelevant.

By the time Carve started autofocus cameras were in their ascendancy, the legendary EOS1N came out late in ’94, and that and the EOS3 were the default pairing in most surf photog’s arsenal. A spare body was essential in those days as things weren’t as reliable as they are now. A lot more moving parts to go wrong, especially when being bashed around by travel.

The last great film camera came with the new century, debuting in 2000, was the EOS1V, a £1500 beast that could shoot a whole roll of 36 frames in 3.6 seconds. Which when that roll of slide film cost you £10 to buy and process was pretty painful.

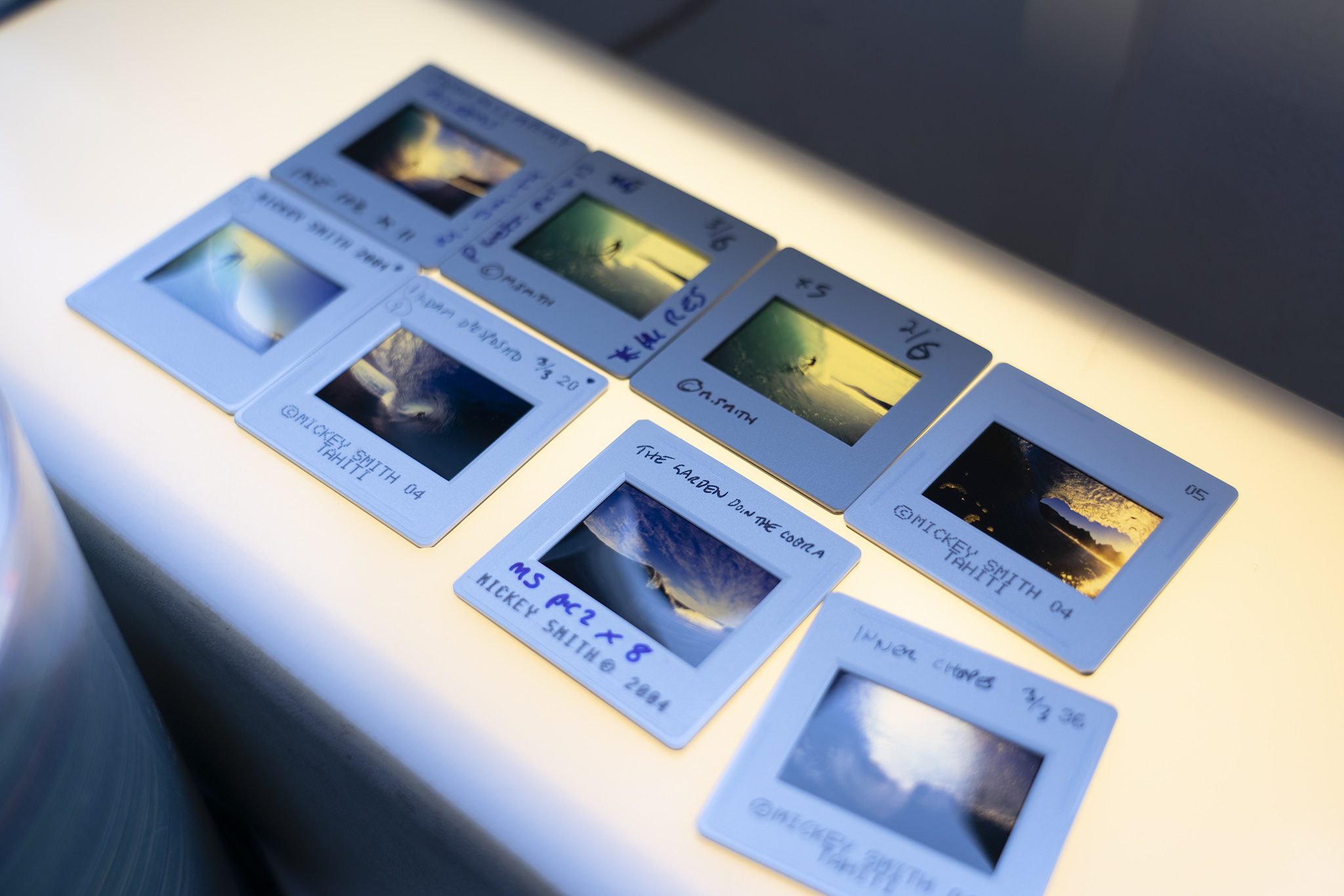

Consider that for a moment, when you are getting the hump over the price of a memory card, one roll of 36 Fuji Provia/Velvia slide film cost you £10. A big trip, like a Hawaiian season, you’d take a minimum 100 rolls, typically 200. So that’s a grand or two up front before you’ve even started. No instant review, no way of knowing if you’d got the exposure right, just fingers crossed you’d nailed the moment of the season. No fixing stuff in post if you’d forked it up. This was why every photog lived with a light meter dangling off their neck on a lanyard. A light meter was your best friend; especially when shooting in Europe.

The film investment was worth it, if you were good, as surf mags were how we got our dose of what was going on. Sure it was a month between Pipe going off and you seeing it in the mags but it was a gentler, less immediate time, the only reason you went online was to check your email and the forecast WAM charts.

Getting shots into the mags was also a massive pain the derriere. These days you can WeTransfer a raw file from pretty much anywhere in the world where there’s a mobile signal seconds after shooting it.

In the ‘90s you could feasibly shoot a roll in the morning, hot foot it to a lab, pay the extra for two-hour processing, and have your slides by mid-arvo. If you then needed that shot to be somewhere ASAP, it then required to be drum scanned. Generally at a repro lab, by geeks using an expensive machine where your precious slide would be coated in oil, then scanned at £40 per slide for a scan big enough to go double spread in a mag.

So. Let’s add that up, shall we? £10 for the roll and processing, travel costs to the lab, plus £40 for ONE FORKING IMAGE. Considering that surf mags paid £50 per page then it will come as no surprise that not many folks were getting their own scans done.

Getting a drum scan, which is what the mag would do anyway if they used your image, was a lifesaver. As it meant you didn’t have to FedEx your slides to one mag, who’d sit on the shots for a month before sending them back so you could FedEx them somewhere else at £50 a pop. But that was the way of things, sell a trip or banger of a shot to one mag in one country then try and sell on to the US, Oz, France, Spain, South Africa, etc. Syndicating to the many mags that used to exist was the key to making coin. Same shot, ran five times equals ch-ching. Or the motherlode get an ad shot with one of the brands; the elusive worldwide buyout would net you north of $3000.

Of course, sending slides by courier meant they got lost, damaged or destroyed. The internet made everyone’s lives easier as it has to this day. That said sending 40MP high res scans via dial-up internet to an FTP was an utter balls.

The ‘90s ended with the first volley across the bows of the good ship print media with the Hardcloud, Swell and Bluetorch episode. Big league, well-financed US surf websites headhunted the best people from the mags and basically said ‘the internet is the future’. The sites looked sick, but the internet speed for most of the world wasn’t up to it, the video was far from easy, and they’d forgot to figure in any way of actually making money. A brief bubble saw a lot of journalists and photographers nursing a scorch mark in their wallets where they’d been promised the farm and never got paid.

The internet went back to being where you looked at weather charts, and message boards and surf photographers of a certain age were generally found to be moaning, a lot, about this new, fangled Digital photography.

The earliest commercial digital camera was the Kodak EOS DCS3 that came out in July 1995, and it was all of 1.3MP, so only of use for newsprint guys. The Kodak EOS D6000 that hit at the end of 1998 was a game-changing 6MP; useful and the press agencies with deep pockets started to adopt it.

The view in surfing was it would never catch on. The quality wasn’t there. The holy grail of a big drum scan from Velvia was going to take some beating. But the writing was on the wall, digital photography was the comet, and the processing and repro labs were the dinosaurs. The eco-system that existed for getting images to newspapers and magazines for decades vanished in a matter of years. The cost went down for the mags at least with no need to spend thousands every issue on drum scans and repro but did the photogs fees go up as they were doing more work? What do you think?

By the middle of the noughties, Canon had released the 1D2 and the 20D both 8MP cameras that became the new default. Any photog still refusing to go digital was basically out of a job as with the repro houses gone most mags insisted on digital submissions only.

So for the last 15 years, life has been easier in magazine land, but the romance, anticipation and excitement of shooting film has gone.

Magazine websites and Surfline ticked along, and all was well, Canon delivered its first full frame sensor camera, the phenomenal 5D, in 2005 and then lit a firework under surf photography in 2008 when they brought out the first DSLR that could also do video: the 5DII. The era of hybrid shooting had arrived, and guys like Kai Neville were filming on DSLRs as opposed to video cameras.

But 2008 brought the crash not to mention the iPhone 3G. The wheels came off the surf industry like many others as the world went into recession. Surf photographers felt it hard. Digital photography democratised shooting, bringing a new generation of keen shooters, more competition, new kids giving brands ad shots for a box of clothes rather than a four-figure buyout and the ever-growing spectre of the internet left many adrift. Magazines started closing as print became less relevant. Social Media arrived in the form of MySpace, and attention spans went where the content was free. Surf photography as a profession has never recovered.

Sure there are more people than ever shooting, but the professional surf photographer is a relic. No one can afford to do it anymore when there’s not the magazine support, or amount of mags to sell to, and the brands don’t spend on ads like they did as there are not the mags to put ads in.

All the big money goes to filmers not stills jockeys. They’re all reduced to chucking stuff on Insta and working a real job to pay the bills. Which when the state of the art Canon 1DXII costs five grand and the mighty Sony A7RIII with its ten frames per second of 42MP glory is over three grand you’ve got to wonder about the economics of it all.

Surf photography in 1994 was about doing it for the love as it is now. A few lucky souls have made a living doing it in between times. Throughout Carve’s 25 years the crew that have worked with the mag have been supported with buyouts for shots, money for travel and advice and/or piss taking from the editorial team. They’ve slaved in the harshest environments possible, found new spots and put themselves in harm’s way to get the shot. To nail a double spread that gets them all of a £100.

Helping new guys has always been vital, where there’s undeniable talent we push in the right direction when the shots are bangers they’re eligible for P1 even if it’s their first submission to the mag (like Gabby Zagni and Conor Flan’ last year). The roster changes as people come and go but Carve wouldn’t be where it is today without the stellar work of Alex Williams, Mike Searle, Chris Power, Stu Norton, Mickey Smith, Will Bailey, Bosko, Swilly, The Gill, Ester Spears, Tim McKenna, Chris van Lennep, Pete Frieden and many more heroes with wonky spines and bad shoulders from carrying too much camera guff around the world.

As for what’s next? Thankfully the camera arms race is nearly at an end. It’s plateaued, so no need for a new camera and water housing every two years as it has been for a long time. Cameras like the Sony A7RIII and A9 (which can shoot 20fps with near flawless autofocus) means that missing the decisive moment is not an option. The only limit is your vision. Making money to pay for these expensive cameras is the tricky bit. Carve still pays for shots, as any real magazine does, but you’ve got to nail a good few main features a year to make a decent dent in your credit card bills. The brands still need awesome imagery for their own channels and with the film costs gone just shooting for shits and giggles with your mates isn’t as painful as it was. Documenting surfing is fun, that’s why we’re here, that’s why we’ve always been here. The methods change, but the song remains the same. Getting out there, looking around the next corner and hopefully scoring and then sharing the stoke with you lot.

Words and surf photos by Sharpy.

First published in Carve issue 194.