By Sharpy

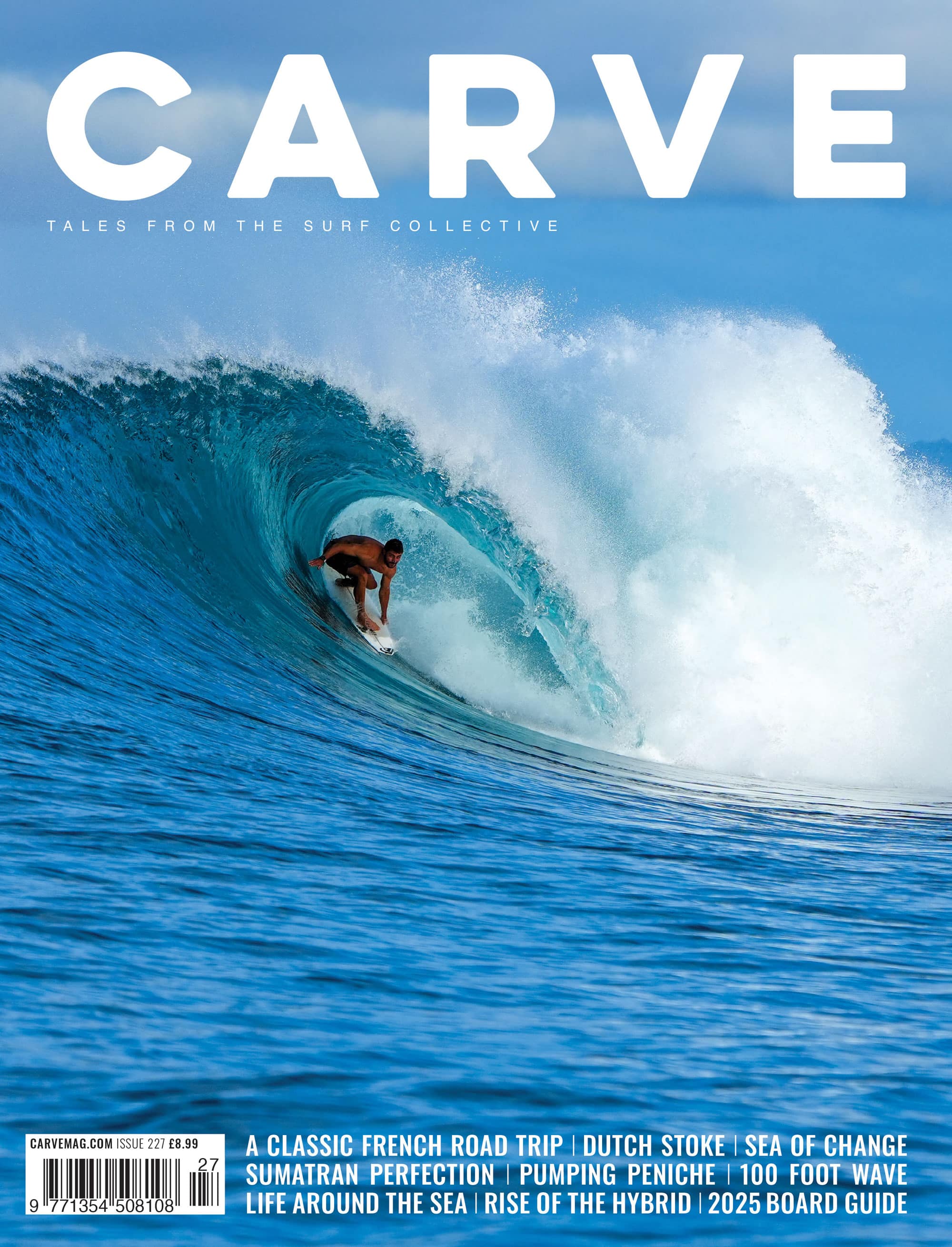

You probably don’t think too much about the surf photos when you’re flicking through magazines or scrolling your Insty, yes they look nice, they can be inspirational and they make you want to go surf or travel but you rarely think about the actual photo and how it was achieved.

Because somewhere out there is a photographer who shot it, a photographer that has dedicated his life to his art, a photographer eating a lot more noodles than steak, a photographer that’s suffered not surfing the best waves he or she has ever seen just to take photos.

American photographer Jeff Divine once said, “Surf photography is starvation on the road to madness”. So you really should be thankful that this strange, often slightly eccentric, sometimes officially mental, noble breed are so obsessed with getting the shot that they keep doing so even though they could make more money slinging burgers in McDonald’s.

The current crop of UK shooters: Nunn, Sharpy, Smith, Lacey, Gartside et al are the product of nearly eighty years of progression. Nearly eight decades of creativity behind the lens from maverick geniuses that have pioneered techniques in and out of the water; it has been these guys out-of-the-box thinking that has got us to where we are today. Combine these creative minds with the ongoing technological revolution that has seen one hundred years of manual focus replaced by auto focusing and film emulsion replaced by zeros and ones and you get to the current stellar, mind-blowing level of photos you seen month in, month out in the magazines and online.

So where did it begin? Who was the first surf photographer? The first photo of somebody with a surfboard dates to 1890, who took it nobody knows (its part of the collection at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu), but it’s quite impressive considering photography was only just getting out its experimental early stages at that time.

The first actual surf photographer documenting surf culture as we know it was the hugely talented Tom Blake. A pioneer in every sense of the word, he revolutionised board construction, was the first man to put a fin on a surfboard and even invented the sailboard (otherwise known as windsurfer) but his main contribution -that sees him regarded as the father of modern surf photography- was his invention of the first water housing for shooting surfing from the water. It is this surfer’s eye view of the action that makes surf photography unique in the sports photography world and Tom Blake first did it in 1930. He got his first spread in the revered National Geographic magazine in 1935.

It was Blake’s early shots, in particular a watershot of Waikiki that appeared in the Los Angeles Times, that inspired the next great, the first dedicated surf photographer- ‘Doc’ Ball. To give him his full name: John Heath ‘Doc’ Ball first started playing about with cameras as a kid around the time of the First World War and started surfing at a time when there were perhaps twenty riders in the whole of California. He had just started taking a few photos of the burgeoning scene in 1929 with a Kodak Autographic given to him by his dentist father’s assistant but it was Blake’s spread in the L.A. Times that appeared in 1931 which made him dedicate his life to recording surfing and surf culture. Not just capturing the action, he recorded the parties, lifestyle, board makers and everything that goes with it. Like his father he qualified as a dentist and seeing as it was the time of the Great Depression money was tight for photographic gear, but this was a time when you made your own boards and shorts and everything was a bit more DIY. So he traded expensive gold dental work for a better camera with the L.A fire chief and in 1937 he built his first ‘water box’ for his new Graflex camera. It was literally a wooden box with a brass handle on the side, to take a photo he had to pop open a little door at the front and close it again before the water got in. Shooting on 3 x 4” film the results were impressive. He laid the foundations of modern surf photography by always exploring new angles and techniques. The Second World War put the brakes on the development of surfing in California as many great surfers went to war and never came back. Doc became a ship dentist in the Pacific theatre and kept himself sane by bodysurfing whenever he could with the new swim fins invented by Owen Churchill; the swim fins photographers use these days have hardly changed in over 60 years. After the war surfing and Doc’s photography picked up where they left off his photos appearing in newspapers, books and even the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Tragedy struck in 1964 when Doc’s house was hit by a flood and drowned his archive but thanks to the fact he gave copies of hundreds of photos away many of his timeless images survive.

The ‘60s were a great time of change as surfing and surf culture took off in the mainstream. The first surf magazines appeared and for the first time surf photographers had like-minded souls to talk to. Guys like Don James, John Severson (the man that founded Surfer mag), Ron Church, Endless Summer creator Bruce Brown and Leroy Grannis were freed up from the restrictions of heavy medium format cameras by the new lightweight 35mm SLR cameras from Canon and Nikon. Grannis in particular defines the early ‘60s shooting water shots at many of Hawaii’s most famous waves and documenting classic Californian swells.

The mid ’60s saw surfing explode into the world’s consciousness through films and music. The transition from the black and white to colour film mirrored the loosening of society’s attitudes from post-war conservatism to the drug-fuelled psychedelia that followed. This era is encapsulated by one of surf photography’s most tragic heroes: Ron Stoner. He didn’t pioneer colour surf photography but he was the first one to master it. From 1965-1967 he was ‘the man’ at Surfer Magazine, his sublime work blew the doors off the competition, his images were simply better than anyone else’s working at the time. He shot everything: action, water, line-ups, portraits and more. Proof if proof were needed: he had the cover shot of Surfer for six consecutive issues. His beautifully composed images and undeniable talent however had shaky foundations. Stoner was schizophrenic and like many at the time had drug problems. Electroshock therapy in the late ‘60s left him virtually catatonic; he’d given up shooting by 1971, was listed as a missing person in 1977 and declared dead in 1994. What happened to him is an enduring, tragic mystery.

Surfing grew through the ‘70s (as board lengths shortened) with big names like Art Brewer and Jeff Divine documenting the birth of professional surfing. The next pioneer came from a tangential source- skateboarding. Warren Bolster is widely regarded as the most influential skate photographer from the sports 1970s heyday. He was among the first to use fisheye lenses, motor drives and strobes to document the four-wheel culture. Inspiring through his work in Skateboarder magazine, amongst others, the young Tony Hawk. Bolster moved to Hawaii in 1978 where he quickly established himself as an accomplished surf photographer. The innovation he bought to skating continued as he pioneered shooting the North Shore surf from helicopters, developed remote-control board mounted cameras and later on shooting half in/half out water shots with extra large custom made domes. Like Stoner his creative genius came from a mind on the edge, and sadly he committed suicide with a shotgun in 2006.

The ’80s saw great leaps in camera technology and an event that fundamentally changed surf photography in the same way the introduction of the leash changed surfing.

Canon got a jump on the opposition in the late ‘70s introducing the A-1 the first SLR camera to feature one of the new fangled microprocessors; a fancy device that ushered in the era of auto-exposure. Previously photog’s used handheld light meters and crude in camera LED light meters to help them make their settings manually. Canon also debuted their manual focus 800mm lens in 1981, which became the surf photographers long lens of choice for the decade.

Big names of the era include the legendary aquanaut Don King. An Olympic standard water polo player credited with being the first heavy water wide-angle guy. Previously in Hawaii when the surf got solid photographers would shoot with a long lens from the relative safety of the channel. King used the new fisheye lenses to shoot big Pipe and Backdoor from spots previously considered suicidal. He leaves a lasting legacy that we’ll come to later. He’s still shooting now but tends to shoot moving pictures for Hollywood (Blue Crush, Castaway, Lost, etc). Another big name with a lasting influence was Larry Moore, otherwise known as Flame, as a photographer he documented the new high-performance surfing in California of kids like Christian Fletcher and as photo editor of Surfing magazine he instilled a professionalism and mentored younger shooters with a passion that still inspires today. He was also a pioneer of the pole cam, a water housing mounted on a minimum 3-foot pole that enabled a whole new perspective. Initially he created the system as a way to shoot back towards land on otherwise backlit Californian afternoons. The device came into its own as aerial surfing progressed through the 80s and 90s with Santa Cruz’s Tony Roberts defining a whole new look in fisheye action photography.

The history of surf photography has been entirely American so far so it’s time for a notable nod to the Australians… Being a professional surf photographer in the early ‘80s involved a high degree of skill. Manually focusing an 800mm lens on a fast-moving surfer was a skill worth its weight in gold. One of the leading proponents of long lens work was Sarge. Paul Sergeant earned good money shooting Formula One and surfing and was instrumental in the careers of many young surfers notably Occy. He was also the first gonzo surf photojournalist- filing contest reports, photos and stories as he circled the globe following the then extremely hedonistic pro tour. He wasn’t just a casual observer, in true gonzo tradition he was often seen leading the charge and like many photographers eventually had to admit he had a drink and drug problem and ended his career in utter disgrace.

The approaching tipping point in camera technology was the death knell for photographers of Sarge’s generation summed up in a word: autofocus.

Pentax brought in the first autofocus SLR 1981, but it was the arrival of Canon’s EOS system in 1987 that was the beginning of the end of the highly skilled surf photographer. With the arrival of their now industry standard 600mm lens in 1988 and the launch of the EOS1 pro camera body in 1989 pin sharp photos were achievable by anyone that could borrow $10,000 and could stomach the ongoing cost of purchasing and processing slide film. The era of the artisan was over and for the next 10-years surf photographers multiplied like flies and the previous high earnings and respect for the old guard disappeared…

The ’90s saw little in the way of technological advancement, the EOS1 eventually morphed into the EOS1V a camera capable of shooting 10 frames a second meaning you could shoot a whole role of 36 frames of slide film in 3.5 seconds and Nikon finally caught up with Canon in all fields beginning the arms race which continues to this day.

The ’90s was the decade of excess, the surf industry boomed and the top photographers made a good living, guys like Brian Bielmann, Hank, Ted Grambeau, Sean Davey and Chris Van Lennep defined our surfing world with many exotic trips opening up Tahiti, the Mentawais and many more destinations.

The big change of the ‘90s was happening in the background. An American student by the name of Thomas Knoll had been slowly coding an image manipulation program on his monochrome Mac. Which finally saw the light of day in 1990 as Photoshop v1.0. The boffins at the camera companies meanwhile were beavering away on digital technology leading to Kodak bringing out the first commercial digital camera in 1991 a 1.3 megapixel bastard son of a Nikon F3, priced at a cool $20,000US. Canon delivered the more realistically priced D30 at $3000US in 2000 at the time 3 megapixels was considered pretty cool. These days we scoff at that on a mobile phone.

The 21st century has seen another sea change in photography. Digital imaging at first was resisted strongly by the surf fraternity. In the same way that board-shaping machines took the soul out of the shaper’s craft photographers saw digital as eroding the last vestiges of their trade. Even with state-of-the-art light meters in the cameras surf photographers still relied on handheld light meters and simply ‘knowing’ what the light level was and setting their cameras accordingly; because even the most expensive camera in the world still gets confused by white-water. Slide film and processing was expensive and if you didn’t expose a slide correctly then it was ruined, there was no such thing as ‘fixing it’ in Photoshop then. Digital cameras removed the cost of film and stripped away and knowledge necessary to get correct exposures. Modern times see cameras that trained monkeys could take surf photos with. But all is not lost…

The digital age has also ushered in a new era of experimentation and democratisation. Photographers that learnt their trade in the era of film continue to prosper, as long as they’ve come up to speed with the computer geekery essential to being a photographer these days, and to get incredible shots all you need is a £300 GoPro so anyone can shoot. Along with the big lens, the camera and waterhousing the other modern essential is a laptop with as much horsepower under the hood as possible teamed with the latest incarnation of Photoshop.

Removing the cost of film means you’re not throwing 20p down the drain every time you take a duff frame.

Digital has opened up a whole new world, especially with flashes, flash has been used in the water for more than 20 years but inspired by skateboarding again guys like Tom Carey have pioneered using remote flashes (where an assistant swims with a flash unit in its own housing) to develop a whole new genre of surf photo, Dustin Humphrey and Dave Nelson also did sterling work to progress this field.

The other big change, inspired by legends like Don King and Chris Van Lennep, was in the field of heavy water photography. An area, at its peak, dominated by bodyboarders- Mickey Smith, Scott Aichner, Tim Jones, Jeff Flindt and Daniel Russo et al all regularly swam in what can only be termed as life-threatening surf to capture mind boggling fisheye images. Every season they pushed each other deeper and bigger at the three key heavy water photo studios- Pipeline, Puerto Escondido and Teahupoo. Where it will stop nobody knows and there’s now a whole new generation like Leroy Bellet and Zak Noyle getting crazy in the heavy salt.

So here we are in 2016, digital cameras and the arms race between the big two camera manufacturers has peaked, with Canon’s full frame cameras hitting 20MP at 14fps (EOS1DXII) which also shoots 60fps 4K. Nikon’s D4S hits 11fps at 16MP and Sony’s stunning mirrorless A7 range is disrupting established theories.

The tit-for-tat war will only continue incrementally and established surf photographers will moan for a bit and only upgrade when something crazy is added.

A technological plateau has been hit as there’s only so many megapixels we need, future models will be eventually hit 50MP and 4K filming capability is becoming standard. Frame rate wise once SLR cameras hit 24fps they are no longer stills cameras … they are movie cameras which is a whole different tax headache. The point where you can grab a mag spread from a video frame grab is already here with RED cams. In the future photographers will be filmers that are good at picking key frames from footage.

Is there anywhere left to go creatively? You’d think every angle had been exhausted. 80-years and hundreds of surf photography devotees later there is still plenty of room for shots that make you stop and draw breath, Laurent Pujol pioneered the ‘behind in the tube’ shot. Building on early deep swimming work by Billy Morris and others getting smashed getting behind surfers in the tube this evolved into surfers carrying housings themselves, and now GoPros, but the Pujol angle is a huge leap and young Aussie Leroy Bellet has taken it further adding flash to the mix. It’s the very definition of suffering for your art. Every shot end’s in an ass kicking.

Where we go from here is anyone’s guess, the only thing you can guarantee is the strange, charmed breed that label themselves surf photog’s will be out there suffering for their art. The money is awful but the office can’t be beat…